Chronology

It was during the summer of 2011 that I decided to have a go at building a pipe organ, or at least to see how far I would get with it. I had then for some time been studying the various websites dedicated to organ building, and seen that pipe organs are indeed not all made in the same way. For me it was crucial to decide on a design and method that would fit my limited experience and the capacity of my workshop. I did not want to spend too much money up front buying materials. I have never been good at making drawings, most things I make are designed along the way, which inevitably means that every now and then I make mistakes and have to go back a few steps. Therefore I set out to look for inexpensive and second hand things I could use.

First steps

From my woodcarving instructor I had obtained some lengths of mahogany, 9x50 mm, which I used for my first pipe. The supply of mahogany I had was enough for maybe 10 pipes only, so I had to find something different. Then I came upon the videos by Phil Radford where he shows how to make pipes using MDF (Medium Density Fibreboard), a very stable, easy to work with, relatively cheap board, available in various thicknesses. This discovery was a breakthrough, and so I made all my pipes of MDF.

After I started making pipes, it soon became clear that repeated blowing of humid air from my lungs was no good for them so I set out to make simple hand operated bellows to which I could attach pipes for testing via plastic tubing.

"Góði hirðirinn" (The good shepherd) is a shop that sells all kinds of usable things that people have brought to the recycling stations. There I found a much needed working desk, made by IKEA as well as a round table top made of laminated beechwood, 4 cm thick and 90 cm in diameter. Altogether the price was equivalent to around 30 US dollars. Out of the beechwood I made , for instance, the pallets and the tops of the "white" keys. A local builder permitted me to pick up pieces of plywood, too small to be useful to them, as well as an old, but unused mahogany door post. I knew that I would need some leather. On a tour to Turkey, during a visit to a leather warehouse, I was given a shopping bag full of discarded clothing leather. From my father in law we had inherited a sizeable roll of furniture leather, so I had more than enough leather.

In my family we had an old oaken dining table, bought in France 30 years ago, which, by this time, nobody had any use for. It had rather stylish legs, which I decided somehow to incorporate into my design. After the table top had been planed it turned out to be ideal for making the frame for the lower section of the organ, and a half-moon slice of it also serves as my signature plate.

In her newly refurbished house, my eldest daughter had a cutout from a kitchen table top, in laminated oak, 42 mm thick, which came in handy. In her house I also found a piece of some unrecognized brown hardwood, quite easy to work with, though. I used it for the "black" keys.

Design ideas

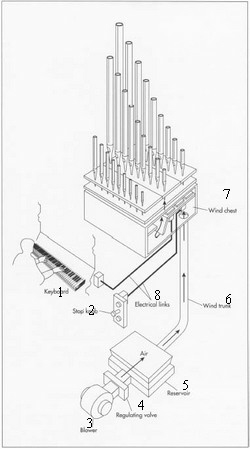

Many hours were spent on studying the various websites dealing with organ building and design, and deciding on a building plan to fit my various limitations, not the least lack of precision woodworking tools and limited space in the garage. I found Matthias Wandel's method of directly coupling the manual keys and the windchest attractive, and soon decided that I would more or less copy his windchest. My keyboard, on the other hand is more inspired by Raphi Giangiulio.

Organ pipe making is a precise science, explained in minutiose detail on the Web, by e.g. Johan Liljencrants and Raphi Giangiulio, but, as shown by Phil Radford, results can be satisfactory even if the science is treated freely. I decided that scaling each pipe with respect to width and wall thickness would be too cumbersome. I set out to make each octave in the same scale, but ended up with making approximately every 6 pipes with identical width. As material I use 4mm, 6mm and 9mm MDF respectively. As reference I used scaling tables from Liljencrants. I decided early on that it should be a one rank organ, the number of pipes to be decided according to my success in making them. In the end I decided on 51 pipe, from c(131Hz), to d''''(2349Hz). The lowest octave has stopped pipes. I did not feel comfortable making much larger pipes in my kind of workshop.

Experiments with prototype

I did not spend much time initially on external design. In fact, for a long time I had no idea how the organ would look in the end. As soon as the number of pipes had been detemined, I also had the dimensions of the keyboard and windchest. As said below, the blower enclosure became bigger than originally intended, and was a detemining factor regarding the footprint of the instrument. But, would I be able to build a reasonably looking, and functioning, manual keyboard, or an airtight windchest? I decided to build a small prototype, a windchest with 7 pallets and a keyboard with 10 keys. The prototype was ready late January 2012, together with some pipes. The test revealed that the windchest design was sound, but I would have to develop a better method to build a presentable keyboard. Probably it was February 17., 2012 when I hooked up the pipes and windchest with plastic tubing and blew them. From that day on I knew that I would succeed with my project.

Construction stages

After the reasonably successful testing of the prototype middle January 2012, I continued making pipes, and had them all done by the end of March. Then I took to building the manual keyboard. I had to improve my method, in order to reach a better result than with the prototype. I also had to take some basic decisions concerning design of the frame. I know absolutely nothing about draftsmanship, but was forced to make some scale drawings, which, actually were enough to ensure that the components fitted together quite reasonably in the end. I built a frame of soft pine, as I suspected that it would have to be redesigned as the work progressed. Which was the case. Frame No 2 was bilt of oak when it's time came. It took around two months, April and May, to finish the keyboard. I followed a plan from Raphi Giangiulio, only with minor changes. For the keystems I used soft pine, actually too soft, something a little more solid would have been easier. The top cover on the "white" keys is 2mm thick beechwood, the "black" keys are made of some brown hardwood, quite easy to work. The keystems have three holes, two for guide pins towards each end, and a hinge in the middle, made of plastic covered curtain spring.

In parallel with this I finished the woodwork around the keyboard. I had the idea of tilting the windchest some 30 ° to give easier access to the plastic tubing underneath it. I wanted to test this concept, so I mounted the prototype windchest in that position, hooked up the pallets with the keystems and attached some pipes with plastic tubing for testing. All went well, so I kept going.

The next job was a full size windchest, which took until the third week of August to finish. I used Matthias Wandel's design, only my pallets are longer, the idea being that I might feed two pipes from the same pallet. At least this time It will not happen. The windchest is a closed box, 22 cm wide and 12 cm high, outside measurements, and the length matches the keyboard. In it's bottom there are holes for plastic tubing, 51 in number, different bore, depending on how big a pipe it shall serve. Within the box there are the pallets, fixed by guide pins and steel springs, and up through the top, which is split in two halves with felt padding in between the halves, come wires, 0.54 mm diameter, hooked up with the keystems. So when a key is pushed, a pallet in the windchest opens and lets air down into the plastic tubing feeding the corresponding pipe. Hopefully, then, the pipe blows it's tone until the key is released. In one of the sides, the windchest has a large hole connecting it to the wind reservoir, supposed to ensure a flow of air of a pressure around 4 hectopascal (= millibar, = cm of water) higher than the environment pressure.

Assembly

By this time I had doubled the insulation around the blower and built a reservoir in the same housing. Then it became clear that the original frame was too narrow. By now I had become so confident in myself and the project, that it seemed natural to make the whole frame and exterior of oak. The top of our french dinner table was planed and cut into 80 mm planks, just enough to build the lower frame, that is up to the keyboard. The upper part, or pipe tower, was initially made of softer wood. But I soon saw a major problem. With a fixed upper frame there would not be any access to the windchest or the inner parts of the organ except by removing so and so many pipes. I hit upon this, in my opinion, brilliant idea to have the upper frame on hinges. After the redesign it can be tilted 45 degrees, thus giving the needed access in case something should go wrong. The new frame had to be oak, so I bought 7 m of 22x15 mm, to finish the frame.

By the end of September, the new pipe tower was ready on it's hinges, the windcest had been installed and the pallets hooked up to the keys by wire straps. I went a few times over the weight needed to press the keys, with a gram gage I had from my days as an IBM customer engineer, in order to ensure even pressure throughout the keyboard. The next step was to put all the pipes in place, which included deciding on the visual display of pipes at the front, running the plastic tubing from pipes to windchest. I encountered some problems finding the required tubing at the neighborhood retailers.

Early November, the local arts an crafts society arranged an Open House weekend, in which I participated, receiving 27 visitors. A neighbour, 10 year old, played a fragment of a sonata, which sounded heavenly in my ears.

Then the organ case remained, in other words all the covering panels. Several ideas concerning looks and finish had been under consideration and were further developed as the work progressed. I decided on birch plywood with oak veneer, supplied by a local workshop. The panels were framed in 10x30 mm oak, some of them embellished with bits of my carving, and patterned with some slots made with the router. On the fifth of March 2013, finally, the organ stood fully assembled in the garage. Most of the panels had still to be varnished, though.Voicing the pipes and fine tuning remained as well.

Blower

I looked around for a used electric blower, but nothing suitable turned up. From Laukhuff in Germany I had a price quotation for a Ventola 6 121 50, their smallest organ blower, but the price was too high for my budget. Instead, a local importer ordered for me a radial blower from C.A. Östberg, type RFE 160C, which seemed to have similar characteristics as the Ventola, at one third the price. After packing the blower in a 16 mm MDF case padded with 2.5 cm rockwool it was still too noisy. A second layer of rockwool and walls of 21 mm thickness around the original case gave a cosiderably lower noise level, which I thought I could live with. The blower gives a static pressure of around 5 hectopascal, but I decided to initially sound my pipes at 3.5 to 4 cm. Initially I used a voltage regulator (a dimmer) to adjust the pressure. Later I made a bellows with a leather membrane. This will be described in more detail in a separate section of this website.